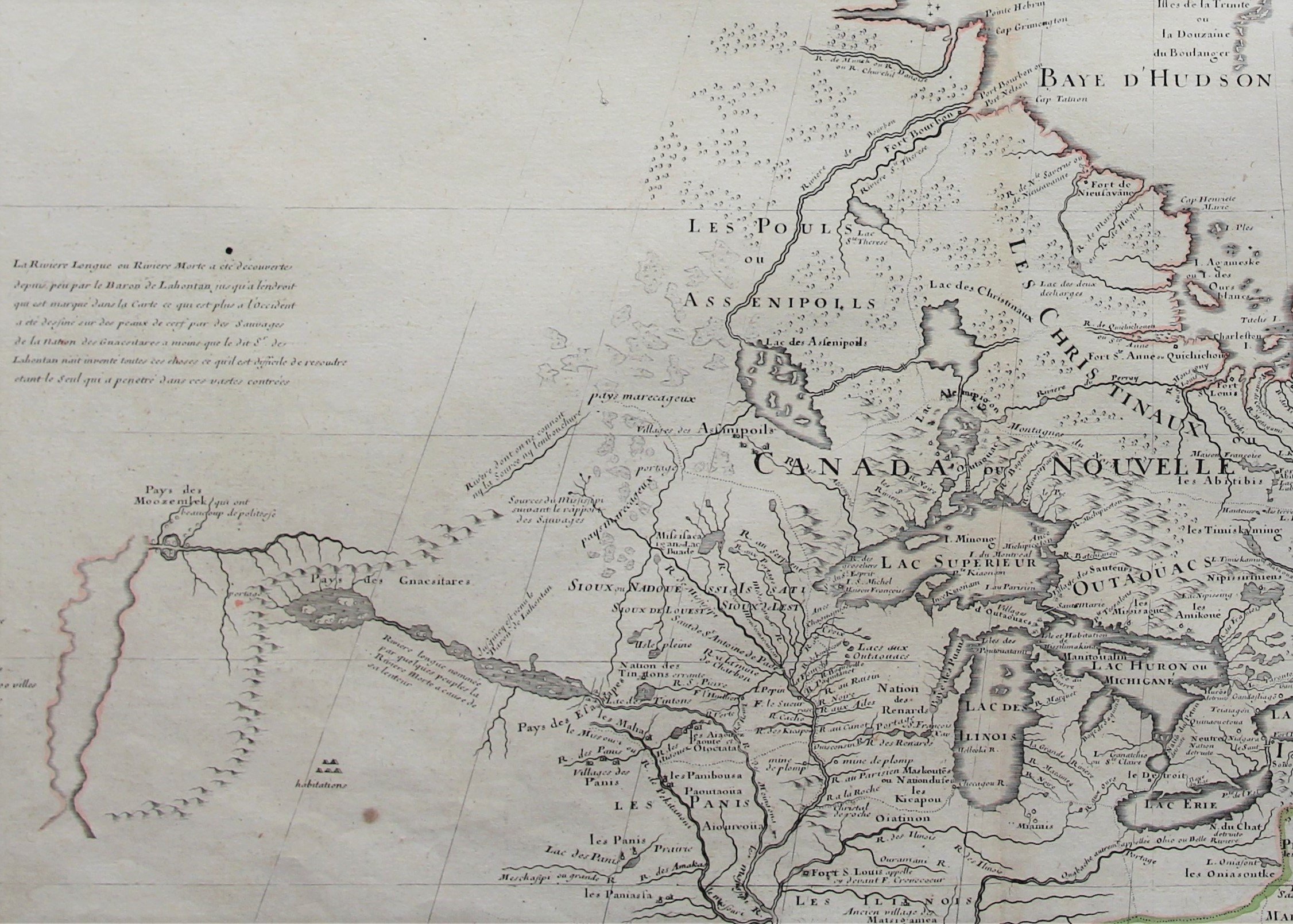

Eastern Canada and the Great Lakes

Seminal

Detail

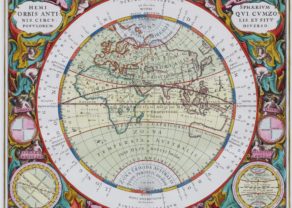

Date of first edition: 1703

Date of this map: ca. 1718 (fifth state)

Dimensions (not including margins): 65 x 49.8 cm

Dimensions (including margins): 67,5 x 51,5 cm

Condition: good. Contemporary outline color on a sheet with a medallion watermark, light soiling, and minor toning along the centerfold. Trimmed to the neatline at bottom center by the bookbinder as issued. Remnants of hinge tape on verso.

Condition rating: A

Verso: blank

Map reference: Kershaw, Early Printed Maps of Canada, 311; cf. Schwartz & Ehrenberg p. 135-137, Plt. 80; Tooley, Mapping America, 37; Wheat, 85; Paullin and Wright, pl. 23A

In stock

de L’isle’s map of Canada and the Great Lakes

This is one of the most outstanding and influential maps of the eighteenth century. It covers Colonial Northeastern United States & Canada, Great Lakes.

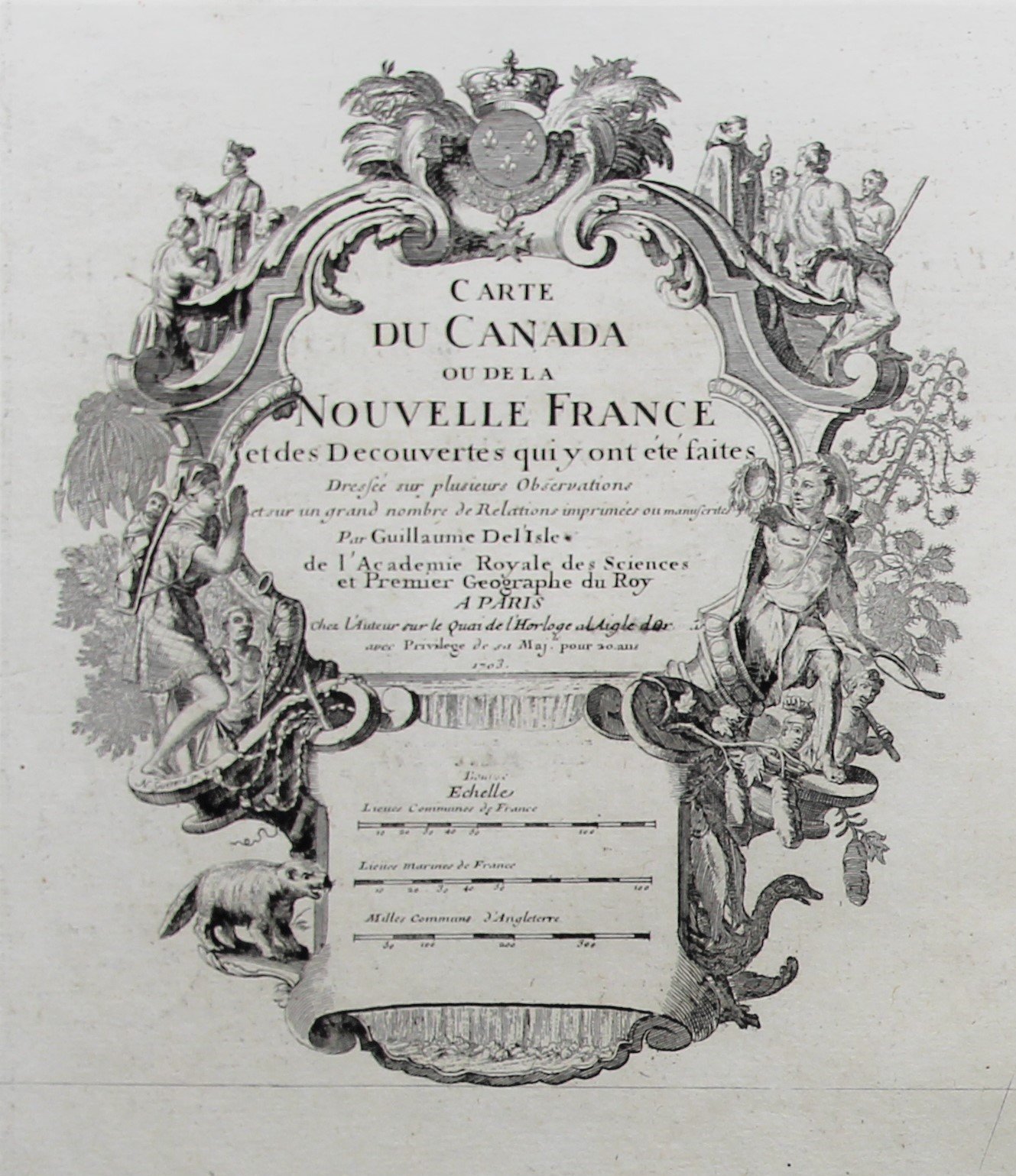

The Great Lakes are portrayed correctly for the first time, and Detroit marks its debut on this map, only two years after its founding. Delisle’s cartography is very meticulous and adds new information from Joliet, Franquelin, and the Jesuit explorers. It correctly positions the Ohio River but confuses its name with the Wabash River. West of the Mississippi Lahontan’s fictitious Riviere Longue is prominently depicted. In Canada special attention is given to the rivers and lakes between Hudson Bay and the St. Lawrence, and Lac de Assenipoils (Lake Winnipeg) connects to Hudson Bay. Sanson’s three islands of the Arctic are retained. Exquisite cartouche with a beaver, natives (one of whom is bearing a scalp), a priest, and friars, engraved by Guerard. This is the fifth state, with de L’isle’s address reading “sur le Quai de l’Horlage a l’Aigle d Or” and “Premier Geographe du Roy” added below his name, published circa 1718.

The map includes one of the earliest references to the Rocky Mountains, the ‘Riviere Longue,’ and other features to the west based on the reports of Louis Armand de lom d’Arce, Baron de Lahontan.

Kershaw on this map

“One of the most outstanding maps of Canada of the 17th and early 18th Centuries . . . De L’Isle’s careful research resulted in the first map of Canada to present the whole of the Great Lakes correctly. In addition, the position of the lakes relative to Hudson’s Bay is also correct, and the Avalon Peninsula is shown much more realistically than on previous maps of Canada. Of considerable significance, the geography of the coastal regions of James and Hudson Bays, together with their major rivers systems, is presented by De L’Isle with a surprising degree of accuracy.”

Baron Lahontan

Lahontan joined the French Marine Corps and was sent to New France in 1683. He quickly learned the Indian languages and became adept in wilderness survival. He was sent to command Fort St. Joseph, near the present site of Port Huron, Michigan. He spent much of his time in America exploring the region. In 1688 he joined a party of Chippewa Indians in a raid on the Iroquois and later abandoned his fort and went to Michilimackinac. During the following winter he explored the upper Mississippi valley where he allegedly discovered the “Longue River”. After several other adventures, including a successful attack on five English frigates in the Gulf of St. Lawrence, he eventually deserted the French military and returned to Europe.

Lahontan’s report of his discovery of the “Longue River” (from the Mississippi to a great range of mountains in the west), along with a short pass through the mountains from which another river flowed (presumably) into the Pacific. He included accounts of Indian tribes who lived on islands in a great lake near the source of the river, and tales of crocodiles filling the waterways. He also used the book, in the form of a dialogue with an Indian named Adorio (The Rat), for a controversial attack on what were then the accepted doctrines of Christianity. While Lahontan’s Longue River proved mythical, the reference to and depiction of the Rocky Mountains by de L’Isle is believed to be the first depiction on a printed map.

de L’Isle’s skeptic look at the Transmississippi West

Although de L’isle depicts the river and indicates the point at which the Baron de Lahontan’s journey is supposed to have ended and the point his reports from Native American information began. De L’Isle himself is skeptical, stating: “…a moins que le dit Sr. de Lahonton n’ait invente tout ces choses ce quil est difficile de resoudre etant le seul qui a penetre dans cest vastes contrees” (“Unless the Seigneur de Lahonton has invented all of these things, which is difficult to resolve, he being the only one who has penetrated this vast land.”) The map includes a note referring to a large body of salt water to the west–“…sur la quelle ils navigant avec de grands bateaux“-a possible, early reference to the Great Salt Lake or a tantalizing hint of access to the Pacific.

De L’Isle studied at the French Maritime Ministry from 1700 to 1703, during which time he took extensive notes on the work of the Jesuit Missionaries, including Franquelin, Jolliet and others. Karpinksi notes that the fruits of de L’Isle’s substantial efforts are born out by the great improvements in the mapping of the 5 Great Lakes and other parts of the map. The information reported by Lahontan is in evidence in the Western part of the map and discussed in a lengthy annotation. Excellent detail on the sources of the Mississippi and the regions around the Hudson and the Great Lakes.

A landmark

It is considered a landmark in map-making for three reasons:

- It is the first map of New France to depict the lines of latitude and longitude pretty accurately.

- It became an evolving map as it was updated up until 1790, despite the fact that de L’isle died in 1726.

- De L’isle drew it without ever setting foot on the North American continent.

Original title: Carte du Canada ou de la Nouvelle France et des Decouvertes qui y ont ete Faites Dressee sur Plusieurs Observations et sur un Grand Nombre de Relations Imprimees ou Manuscrites

Scale ca. 1:9,000,000.