Northern Japan – Carte des decouvertes au Nord du Japon

Towards the end of the world

Detail

Date of this edition: 1797

Dimensions (not including margins): 49,5 x 68,5 cm

Condition: excellent. Sharp copper engraving printed on paper. Wide margins, good impression. Superbly hand coloured.

Condition rating: A+

Verso: blank

Reference: Lazar, Margarete. “The Manuscript Maps of Engelbert Kaempfer.” Imago Mundi 34 (1982): 66-71; “Galaup, Jean-Francois de (comte de La Perouse)” in Encyclopedia of Exploration, Vol. I, eds. Carl Waldman and Alan Wexler (New York: Facts on File, Inc.,2004), 246-8.

From: Atlas du Voyage de La Perouse (Paris: L’Imprimerie de la Republique, An V, 1797).

In stock

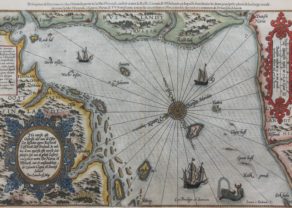

Important Chart of Northern Japan Illustrating Early Dutch Discoveries as Recorded by the Lost La Perouse Expedition

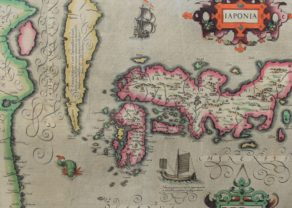

Oriented with west at the top, this chart shows the discoveries made by the Dutch ships Kastrikum (Castricum) and Breskens in 1643 in the northern parts of Japan.

The map was made at the end of the eighteenth century by Jean-Francois de Galaup, the comte de La Perouse, France’s most famous explorer. It was intended to communicate information about a little known area of the world, the northern Pacific. To the left is the coast of Japan, while to the right (north) are coastlines labeled as Jesoga-Sima, Staten Eylandt, and Compagnies Landt. Below is a view of the latter as seen from on deck a ship on the approach to the land.

In the upper center are two inset maps which show sections of maps previously published by Scheuchzer and Kampfer. Johan Caspar Scheuchzer (1702-1729) was a Swiss scholar who specialized in Japan. He translated the manuscript of Engelbert Kaempfer (1651-1716), a German physician who toured Russia, Persia, India, Southeast Asia and Japan from 1683 to 1693. The work was published as History of Japan in 1727. Both men had drawn sketches of Japan that were published posthumously which served as the basis for this map.

Compagnies Land and geographic enigmas in the North Pacific

The map includes the coastlines of three lands north of Japan, Jesoga-Sima, Staten Eylandt, and Compagnies Landt. Jesoga-Sima is a reference to Jesso, a feature included on many eighteenth-century maps. Historically, Eso (Jesso, Yedso, Yesso) refers to the island of Hokkaido. It varies on maps from a small island to a near-continent sized mass that stretches from Asia to Alaska.

La Perouse also mentions Dutch discoveries in 1643, which indicates that his understanding of Jesso is tied to two other North Pacific chimeras, Gamaland and Compagnies Land. Juan, the grandson of Vasco de Gama, was a Portuguese navigator who was accused of illegal trading with the Spanish in the East Indies. Gama fled and sailed from Macau to Japan in the later sixteenth century. He then struck out east, across the Pacific, and supposedly saw lands in the North Pacific. These lands were initially shown as small islands on Portuguese charts, but ballooned into a continent-sized landmass in later representations.

Several voyagers sought out de Gama’s lands, including the Dutchmen Matthijs Hendrickszoon Quast in 1639 and Maarten Gerritszoon Vries in 1643. Vries commanded the Castricum, while Hendrick Cornelisz Schaep was in charge of the Breskens. These are the ships mentioned in the title of the map.

Compagnies Land, along with Staten Land, were islands sighted by Vries on his 1643 voyage. He named the island for the Dutch States General (Staten Land) and for the Dutch East India Company (VOC) (Compagnies, or Company’s Land). In reality, he had re-discovered two of the Kuril Islands. However, other mapmakers latched onto Compagnies Land in particular, enlarging and merging it with Yesso and/or Gamaland. It is clear La Perouse had Vries and his voyage in mind, as a strait between Staten Eylandt and Compagnies Landt is named Stretto Vriez.

In the mid-eighteenth century, Vitus Bering, a Danish explorer in Russian employ, and James Cook would both check the area and find nothing. La Perouse also sought the huge islands, but found only the small islands shown here, putting to rest the myth of the continent-sized dream lands.

The La Perouse Expedition and Atlas

Inspired by the success and popularity of James Cook’s three voyages, the French planned their own expedition of Pacific discovery in 1785. The commander chosen by Louis XVI to lead the voyage was Jean-Francois de Galaup, comte de La Perouse (1741-ca. 1788). At 15, La Perouse had joined the French Navy as a marine and he enjoyed promotion during the actions of the Seven Years’ War. In the 1770s he served in the Indian Ocean and, in the early 1780s, in Hudson’s Bay during the American Revolution.

La Perouse was to carry on where Cook left off, exploring the western Pacific and continuing to look for a Northwest Passage. He set off from Brest in August of 1785 in command of the Boussole, with Paul-Antoine-Marie Fleuriot de Langle accompanying in the Astrolabe. They headed across the Atlantic, round Cape Horn, with stops at Easter Island and Hawaii. From there, La Perouse navigated to the coast of what is now Alaska, where La Perouse agreed with Cook that there was no Northwest Passage entrance along that coastline.

La Perouse returned south, to Monterey Bay, California, before heading across the Pacific to Macao, then a Portuguese colony. From there, they sailed to Manila, Formosa (Taiwan), the Ryukyu Islands, and between Korea and Japan. It was here that his men made the observations that contributed to this map, of the Japanese island of Hokkaido, Sakhalin Island, and the Kurils. Then, La Perouse ventured farther north to Petropavlovsk on the Kamchatka Peninsula.

Having received word of a new British colony in southeast Australia, La Perouse sailed south, searching for the long misplaced Solomon Islands on the way. At Tutuila, in what is now American Samoa, 12 of the crew were killed in an altercation with indigenous peoples. This was not the last misfortune to fall upon the voyage.

La Perouse arrived at Botany Bay, now Sydney, in January of 1788, where he left letters and his journals. He observed the nascent penal colony and then returned to the western Pacific, near the Gulf of Carpentaria. En route he and his ships disappeared without a trace. Two years later, in 1791, Antoine-Raymond-Joseph de Bruni, chevalier d’Entrecasteaux, was sent to find out what had happened to La Perouse and his men. He made several discoveries but not anything related to La Perouse’s ships or crew. In 1826, an Irish captain, Peter Dillon, was in the Santa Cruz group and came across several French swords which locals told him came from two large ships that had broken up on reefs.

Only in 1828 did another French expedition, commanded by Jules-Sebastien-Cesar Dumont D’Urville, locate traces of the Astrolabe near the island of Vanikoro (part of the Solomon Islands). It seems La Perouse and his ships wrecked on the island; several survivors were killed by the local population, while others may have tried to sail in a small craft to Australia, but none were ever found. In 1964, archaeologists located the wreck of the Boussole in the waters off Vanikoro.

Partially because of the scope of the voyage and the popularity of Pacific exploration, and partially because of his mysterious disappearance, La Perouse was the most famous French explorer then and continues to be to this day.

His voyage’s story was told based on materials he managed to send back from Macao, Petropavlovsk, and Botany Bay. These journals and manuscripts, including many charts, made up the source material for an account of the voyage published in Paris in 1797. An accompanying atlas was published ca. 1797. This is plate is number 47 from the famous atlas and it helped to clarify actual geography from fables.